Indigenous Rights Solidarity Group (IRSG)

The Indigenous Rights Solidarity Group has members from Bathurst, Bloor Street and Trinity-St. Paul’s United Churches.

Below is a sampling of some of our past and ongoing activities:

- Creation of the Heart Garden recognizing the history and on-going impact of residential schools

- Annual recognition of Orange Shirt Day with ceremony in the Heart Garden

- Creation of the Treaty Recognition Garden, acknowledging the history of dispossession of Indigenous peoples from their land

- Annual “Paying Rent” service: “rent” collection is a symbolic recognition of the unjust dispossession of Indigenous peoples from their land, and a reflection of our desire for a more equitable sharing with First Nations in the future. The collection goes to two Indigenous agencies: Na-Me-Res and the Native Women’s Resource Centre

- Participation in solidarity actions with the families of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

- A lending library of books on Indigenous subjects.

Treaty Recognition

Heart Garden

Naming Ceremony

Treaty Recognition

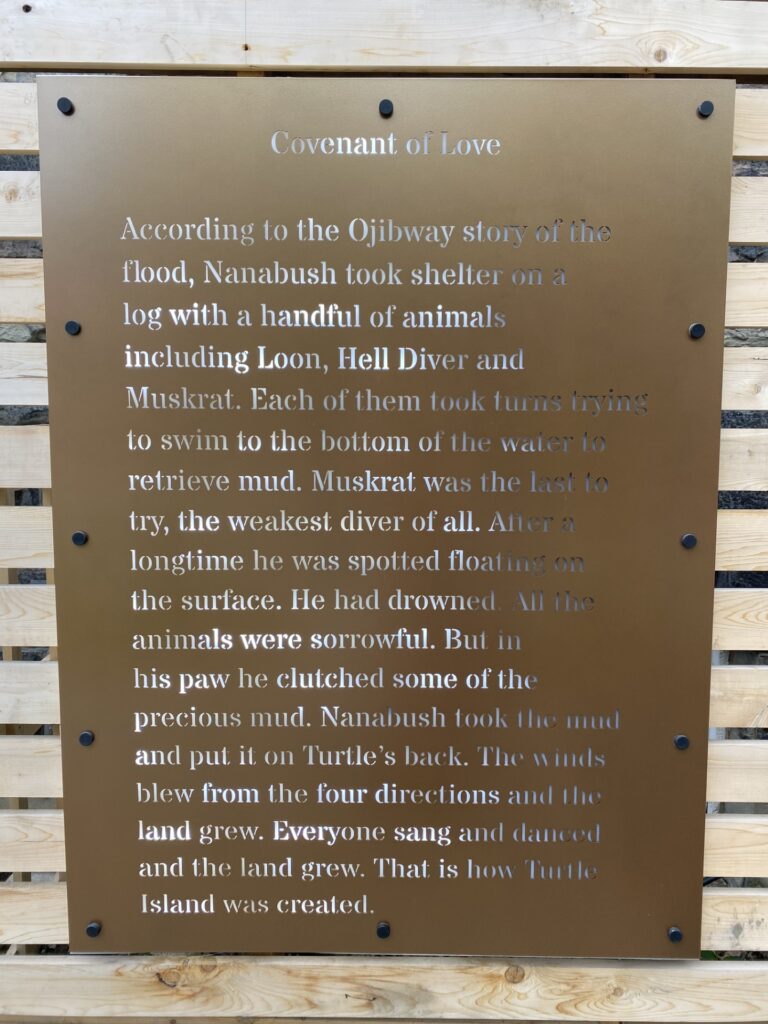

Covenant of Love (first plaque in the Treaty Recognition garden)

A more complete version of the Ojibway story of the flood can be found in The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway by Edward Benton-Banai.

We consulted elder Jacque Lavalley for help in abbreviating the story as it appears in the garden.

The artwork in the garden illustrating this story was originally created for the video “The Ojibway Creation Story”, which was a part of the Ningwakwe Learning Press’ book Fire and Water: Ojibway Teachings and Today’s Duties. Spring Water Woman ~ Dolly Asinnewe is the artist. Dolly is Anishnaabe kwe from Wikwemikong, Ontario, a visual artist, graphic Illustrator, amateur photographer and beadworker. Dolly graciously gave permission to use two of her illustrations in the Heart Garden.

A version of the Story of the Flood is the opening chapter in Robin Kimmerer’s book Braiding Sweetgrass : Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. In her commentary on the story Kimmerer notes the difference between the Western and Native world views:

“In the Western tradition there is a recognized hierarchy of beings, with, of course, the human being on top – the pinnacle of evolution, the darling of Creation – and the plants at the bottom. But in Native ways of knowing, human people are often referred to as the ‘younger brothers of Creation.’ We say that humans have the least experience with how to live and thus the most to learn – we must look to our teachers among the other species for guidance. Their wisdom is apparent in the way they live. They teach by example. They’ve been on the earth far longer than we have been, and have had time to figure things out.” (Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013), p. 9

The values of kinship and consent embedded in the Indigenous worldview inform the Indigenous understanding of treaty making.

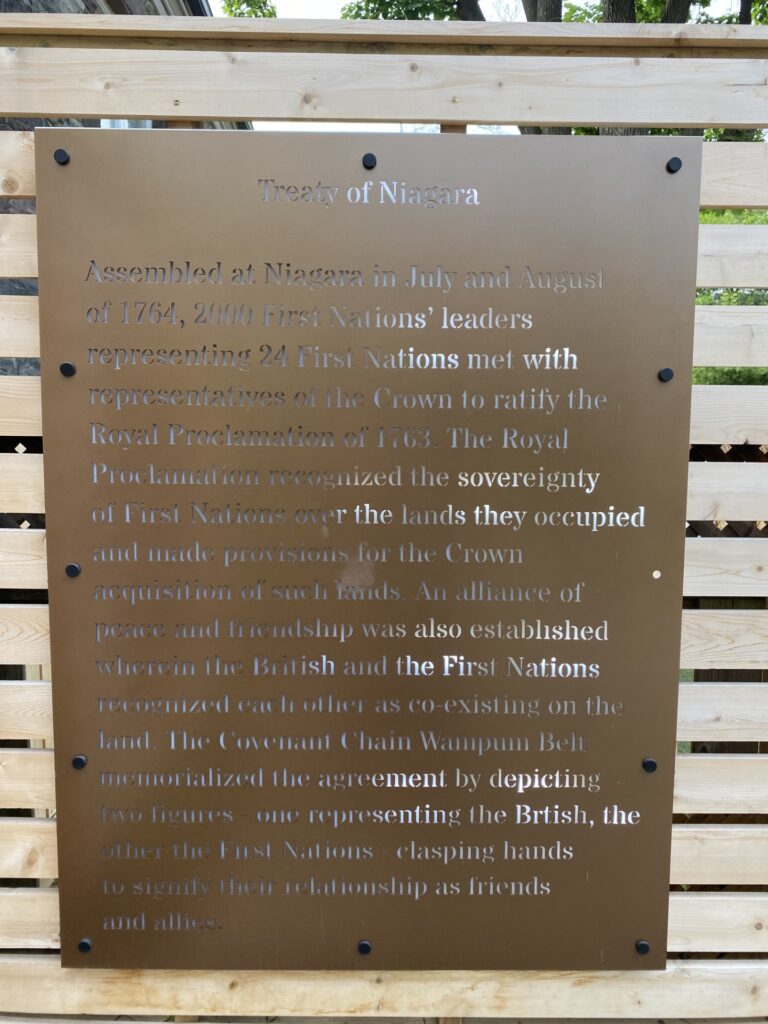

Treaty of Niagara (second plaque in the Treaty Recognition garden)

Treaty Relationships and the Covenant Chain

When European and Indigenous civilizations started interacting with each other, they needed a framework to respect their independent social, political, economic and legal systems. Such frameworks already existed within Indigenous societies and were extended to European settlers: Treaty Relationships.

Treaty Primer from the Mocassin Identifier Project of the Mississaugas of the Credit. Click here to read.

Significance of the Treaty of Niagara: Click here to read.

While Canada does not officially recognize the 1764 Treaty of Niagara, First Nations see it as foundational to their understanding of the Royal Proclamation as well as establishing a nation-to-nation relationship with the British Crown. According to John Borrows, an Anishinaabe legal scholar and theorist, the Royal Proclamation cannot be understood without the presence of the Niagara Treaty. Simply, the Proclamation by itself only represents the Crown’s understanding of the relationship; together, the Proclamation and the Treaty of Niagara represent a more rounded understanding of the Indigenous-Crown relationship. In fact, Borrows notes that, taken together, the two documents mandate non-interference of the Crown in Indigenous governance and lands as well as recognizing Indigenous sovereignty. The Crown, however, disagrees.

Further background: the following article by Nathan Tidridge provides a summary of an essay by Professor John Burrows titled “Wampum at Niagara: The Royal Proclamation, Canadian Legal History, and Self-Government”: https://www.tidridge.com/uploads/3/8/4/1/3841927/the_treaty_of_niagara.pdf

Photo of the 1764 Treaty of Niagara Belt, by Ward P. Laforme Jr.

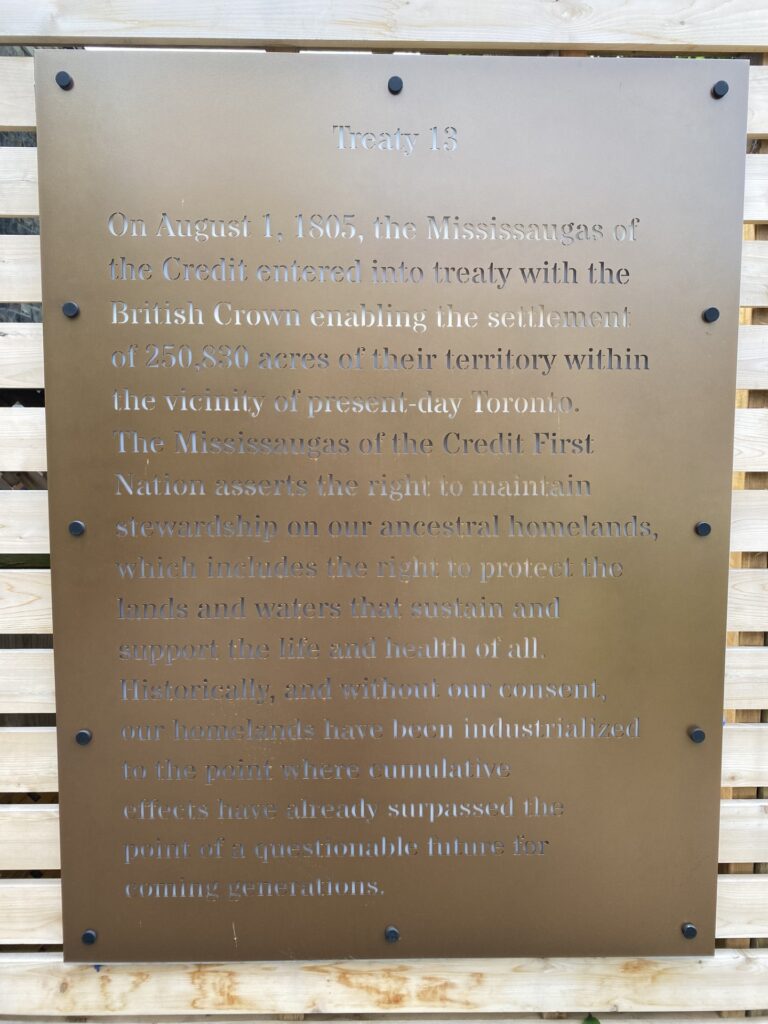

Treaty 13 (third plaque in the Treaty Recognition garden)

Documentation on the Toronto Purchase Treaty, No. 13 (1805) from the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation website. Click here. Map is the projection approved by the First Nation, provided by Darin P. Wybenga, Heritage Interpreter for the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation.

Further historical background from Talking Treaties:

- https://talkingtreaties.ca/treaties-for-torontonians/toronto-purchase/1787

- https://talkingtreaties.ca/treaties-for-torontonians/toronto-purchase/confirmation-1805

The 2010 Toronto Purchase Specific Claim: Arriving at an Agreement

Paying Rent

“Paying Rent” is a symbolic recognition of the unjust dispossession of Indigenous peoples from their land, and a reflection of our desire for a more equitable sharing with First Nations in the future.

“Paying Rent” collections are a biannual event in our church life, and are part of special services: the June service takes place during national Aboriginal celebrations, and the November service during Treaty Recognition Week in Ontario.

The collection is a way to build relationship through a concrete act of repentance, and is split between the Native Men’s Residence and the Native Women’s Resource Centre.

Through a culture-based approach that addresses the holistic needs of its clients, Na-Me-Res’ (Native Men’s Residence) mission is to provide temporary, transitional and permanent housing to Aboriginal men experiencing homelessness in Toronto while providing outreach and support services to the broader Aboriginal homeless population.

During our first meeting with Na-Me-Res staff, we had a conversation about the history of settlers taking the land, residential schools, and continued racism and inequality. We learned that two of Na-Me-Res’ programmes target individuals suffering from mental health and addictions that can be directly attributed to the continuing social problems stemming from this history. Mino Kaajigoowin (finding something good – finding the good to find self or direction in life) and Ngim Kowa Njichaag (reclaiming the Spirit) address mental health and addiction issues, cultural loss and healing through traditional culture.

Through this relationship we were also introduced to elder Jacqui Lavalley who has helped us with our Heart Garden, and have been invited to volunteer at their annual Pow Wow at Fort York.

The Native Women’s Resource Centre of Toronto provides a safe and welcoming environment for all Aboriginal women and their children in the Greater Toronto Area. Programs fall under six broad categories: Housing, Families, Advocacy, Employment, Education, and Youth. A variety of Cultural Activities are offered for clients and the general public, including the annual Minaake Awards, Sisters In Spirit Vigil, and Winter Solstice.

At our first meeting, we had a tour of the building. What impressed us was that people who were formerly clients had become centre leaders. As we watched the children of clients play and learn, we heard from social workers who support homeless women in their dealings with Family Services. The work readiness programs are fully subscribed. We left convinced that a very busy Indigenous staff were healing many, many women to the benefit of subsequent generations.

The Heart Garden

“The establishment and operation of residential schools were a central element of [Canada’s Aboriginal] policy, which can best be described as ‘cultural genocide’…Canada separated children from their parents…not to educate them, but primarily to break their link to their culture and identity”

In 1986 the United Church of Canada apologized to Indigenous peoples for our part in the history of colonization: “We tried to make you like us and in so doing we helped destroy the vision that made you what you were. As a result, you and we are poorer and the image of the Creator in us is twisted, blurred and we are not what we are meant by God to be.” In 1998 the United Church apologized for the pain and suffering that our church’s involvement in the Indian Residential School System caused.

The call to create Heart Gardens came from the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society as the TRC came to a close in 2015. “Honouring Memories, Planting Dreams” invites individuals and organizations to join in reconciliation by planting Heart Gardens in their communities.

Our Heart Garden is situated next to Trinity-St. Paul’s United Church, which was completed in 1889. The building is an expression of the prestige and confidence of this Christian community in the same era in which government and church were confidently embarking on a project to end the Indigenous way of life. Christian churches played a central role in denigrating this spiritual way of being; now, with an attitude of humility, we seek to learn from it as a source of healing from our own captivity to colonialism.

“Help us to open our hearts to others, pay attention to our thoughts, words and actions, notice when we have hurt others and change our behaviour in the future. With this Heart Garden we honour the children who were lost or survived the Indian Residential School System.” This was our prayer with the children of Trinity-St. Paul’s, Bathurst and Bloor Street United churches as we made “hearts” that were sent to the closing ceremony of the TRC in Ottawa and planted others in the developing Heart Garden on the northwest side of Trinity-St. Paul’s. Each year since, the children make and laminate hearts to plant in the garden.

The garden is in the form of a medicine wheel. Over the years we have been working with Jacqui Lavalley, an Anishinaabe elder, to guide us in planting the four sacred medicines – tobacco, sage, cedar and sweet grass. Jacqui also leads us in Anishinaabe ceremony and teachings.

In the summer of 2019, several glacial erratic boulders were unearthed during the construction of the parkette across the street from the garden. The city gifted us with two of them. In Indigenous culture stones are regarded as Grandfathers, wise from their countless lifetimes. About the same time we came upon a poem by Métis author Katherena Vermette: “an other story” evokes the ancient life cycles of the earth. Over the summer of 2020 Anishinaabe artist Solomon King built the wooden screens that hold the poem, and installed stonework for the garden. In the fall of 2020 the garden was completed.

“We are here to honour our ancestors and make a place for our children. It is the only job that matters.” – Katherena Vermette

We acknowledge the generous financial support of Trinity-St Paul’s United Church, the United Church of Canada Foundation, Bloor Street United Church and individual donors which contributed to the realization of this project.

This project is supported by the My Main Street program, the Canadian Urban Institute, and the Government of Canada through the Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario (FedDev Ontario).

Naming Ceremonies

“As a young boy, huddled over a hot bowl of soup on the upper balcony and protected from the cold, I asked my father why we came to Trinity St. Paul’s. He answered…because we are safe here. We are in the House of God. I ask him ‘who is God’ and he replied ‘everything'” (James Carpenter, AHT Traditional Healer)

On September 23rd, Traditional Healer James Carpenter from Anishnawbe Health Toronto (AHT), the Indigenous Community Health Centre, conducted a Naming Ceremony to identify the spirit underlying an endowment fund established in support of the new home for Anishnawbe Health Center being built near the Distillery District. James identified the spirit name after conducting a sweat lodge with nine TSP members and then dreaming with the tobacco offered by the members at the lodge. Following a pipe ceremony and announcement of the Spirit Name, over 200 TSPers and guests celebrated with a round dance and generous potluck feast that included bannock made by our youth and children with members of the Indigenous community. The Kind Spirit of Trinity St. Paul’s vibrated throughout the sanctuary, dining hall and into the streets with food being carried away to feed people who could not attend.

Direct contributions to the Anishnawbe Health Foundation may be made at www.supportanishnawbe.ca. Named recognition opportunities on the Centre’s donor wall and in the centre are available for pledges of $5,000 or more. For more information, contact jcookson@aht.ca

For more information on The United Church of Canada’s Healing Fund which will also benefit from grants made by Mii-gi-we-Zha-way-nim-Manitoo please visit https://www.united-church.ca/stories/healing-fund-changing-lives